This is the Peabody Library in Baltimore. It makes me wish I lived in Baltimore. This photo is really ubiquitous, but this particular version is from leafar's flikr page, whoever that is. Once in 7th grade our teacher did this exercise where we were supposed to close our eyes and picture an ideal, peaceful place, and if I had seen this picture then, this is what I would have pictured. What I actually pictured was a room with lots of big, sunny windows, shiny parquet floors, salmon-y coral colored walls, bookshelves, and a big beanbag/floor cushion thing upon which I would sit. What would you picture?

This is the Peabody Library in Baltimore. It makes me wish I lived in Baltimore. This photo is really ubiquitous, but this particular version is from leafar's flikr page, whoever that is. Once in 7th grade our teacher did this exercise where we were supposed to close our eyes and picture an ideal, peaceful place, and if I had seen this picture then, this is what I would have pictured. What I actually pictured was a room with lots of big, sunny windows, shiny parquet floors, salmon-y coral colored walls, bookshelves, and a big beanbag/floor cushion thing upon which I would sit. What would you picture? This is Andrew Carnegie, steel magnate and builder of more than 2,500 libraries. I like him. He is the real focus of this essay. Mainly because I went to the Chattanooga Bicentennial Library last week for the first time in forever and before I even walked in, I could smell the library smell - books and carpet and dust and old newspapers and a little disinfectant and the ink from the check-out date stamps. It reminded me of how much I love the library.

This is Andrew Carnegie, steel magnate and builder of more than 2,500 libraries. I like him. He is the real focus of this essay. Mainly because I went to the Chattanooga Bicentennial Library last week for the first time in forever and before I even walked in, I could smell the library smell - books and carpet and dust and old newspapers and a little disinfectant and the ink from the check-out date stamps. It reminded me of how much I love the library.Although libraries are not everyone's favorite place, and I did avoid the one at Auburn as much as I could, (too much fluorescence - further ranting on my hatred of cfl lights and the fact that ambient light in this country will be forever ruined by the year 2012 later) the library makes me happier than most places.

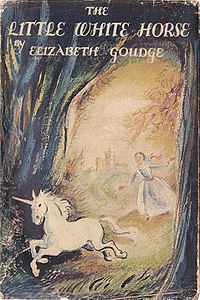

One of the many great things my mother did for me when I was a child was keeping me in constant supply of books of all genres and sizes. I enjoyed nearly complete collections of Nancy Drew and the Boxcar Children, and classics like Little Women, Girl of the Limberlost, Anne of Green Gables, and Narnia. There were also the slightly more obscure tomes like the Five Little Peppers, and the Betsy books (omg, so wonderful I wish I was reading one right now), and All-of-a-Kind Family books, and The Twenty-one Balloons (which I gave all the students in my class last year for Christmas), and Ginger Pye, and a book I stumbled upon at the library called The Little White Horse, which was old and odd and a truly magical story.

I created rituals for myself with some of these books - Little Women I read every year over Christmas from second grade through college, The Little White Horse I read every summer for about as long. Going to the library in and of itself was a ritual for me once the summer began. When I was little, we would park at the Choo Choo and get on the electric shuttle, which would deposit us at the Broad Street entrance of the library, right in front of the giant fountain composed of books made of steel. Then through the doors onto the Brady Bunch-era orange carpet (still there), turning right in front of the information desk constructed out of dark possibly-wood. To get to the children's section, you go up the stairs with the smooth shiny handrails to the second floor.

This convenient photo is from a website called sceniccityscoop.com.

When we got back on the bus, the bus driver would tease me about my giant stack of books (even she could sense my nerdiness.) By the time I was ready for the grown-up section, we had moved to Brainerd and started going to the East Gate library, which was smaller and not as cool, but I still liked it, and would roam the stacks forever. I remember exactly where I found All's Quiet on the Western Front, and Agatha Christie.

Anyhow, all this to say that the library was integral to my childhood and adolescence, and I think I would probably be different if I hadn't had access to all those books. "You are," as Frank Navasky writes about 'The Shop Around the Corner', "what you read." Annie Dillard, in the oft-mentioned An American Childhood, remembers that her father's bookplates stated "Books make the man," over a picture of a ship with full sails. Both true, in my opinion.

From Annie Dillard, I also learned about Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish-born immigrant who came to America with his family as a child and started working at 13. Carnegie, as we know, was the developer of US Steel and played a key role in building our nation's railroads, which in turn dictated a great deal of the development of our nation in general.

As a result of this and some other smart investments, Carnegie amassed an enormous fortune and felt that it was a major responsibility on his part to disperse his "surplus wealth" for the betterment of mankind. "One of the serious obstacles to the improvement of our race is indiscriminate charity," Carnegie once said, and his philanthropy was based on this principle. He believed in giving to the "industrious and ambitious; not those who need everything done for them, but those who, being most anxious and able to help themselves, deserve and will be benefitted by help from others." Ah, indeed, Mr. Carnegie.

As a young man, Carnegie worked for a telegraph company, and his boss would let the workers have access to his private library on Saturdays. Carnegie was endlessly grateful to this man who had given "working boys" the opportunity to acquire knowledge and better themselves. The memory of this gift is likely what inspired Carnegie to choose libraries as one of the chief means of distributing his surplus wealth, for as he said, "I choose free libraries as the best agencies for improving the masses of the people, because they give nothing for nothing. They only help those who help themselves. They never pauperize. They reach the aspiring and open to these chief treasures of the world -- those stored up in books. A taste for reading drives out lower tastes."

What he had gathered from the gift of books had been stepping stones to becoming the person he was, and he felt that enabling others to find those stepping stones was the greatest gift he could give. (Incidentally, he also gave a great deal of money to other things like universities and health care facilities, but libraries were his dearest gift.)

Anyhow, in addition to the more than 2,500 libraries he built around the world, we also have Carnegie to thank for the way libraries work these days. Before he started designing them, going to the library to get a book meant asking a clerk to go back into the closed stacks and pick it up for you. Carnegie wanted people to be able to explore the books, and be pulled in by what they saw, making their own selections to build their stepping stones, so he designed open stacks that people could wander and browse. This concept is key to the library experience, so grazi, Andrew.

His libraries were all beautiful buildings, aesthetically supervised by his secretary, James Bertram. Most feature a prominent entrance reached by a staircase, to symbolize elevation by learning. Each library also generally featured a lantern or lamppost outside, which represented enlightenment. The first library he built was in his hometown of Dunfermline, Scotland, and over the door he had enscribed "Let there be light." Since he was such a classy guy, we will forgive him for what could be taken as an overuse of symbology and appreciate the sentiment.

This is a Carnegie Library in England. As you can see, Andrew insisted that the libraries be beautiful, welcoming places that people would actually want to go into. Very classy.

Carnegie, like many of his fellow titans of industry, became the model for today's philanthropists. The MacArthur Foundation, The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and many others follow his ideal of inspiring people with goals and dreams to better themselves, and to rise above whatever their circumstances might be. I feel like I owe a lot to Andrew Carnegie, and so I felt compelled to write this little ode to him, for which (if you've read this far) I appreciate your indulgence.

Here are some awesome things that Andrew said while he was alive. I wish I could shake his hand:

"Think of yourself as on the threshold of unparalleled success. A whole, clear, glorious life lies before you. Achieve! Achieve!" This is my favorite thing that Andrew said. I feel like it should be emblazoned on the walls of every school in the country. Of course then people would just get used to it and ignore it.

"And while the law of competition may be sometimes hard for the individual, it is best for the race, because it ensures the survival of the fittest in every department." Ah Andrew. It is a shame you aren't around to remind people (government people, especially) about this.

"He that cannot reason is a fool. He that will not is a bigot. He that dare not is a slave." Tell it like it is, Andrew.

"He that cannot reason is a fool. He that will not is a bigot. He that dare not is a slave." Tell it like it is, Andrew.

"There is not such a cradle of democracy upon the earth as the Free Public Library, this republic of letters, where neither rank, office, nor wealth receives the slightest consideration." I really appreciate Andrew's definition of democracy, which rests on the tenet that men are free when they pursue knowledge and achievement by stretching their minds. Seems unique. George Will would approve. And Ron Paul. That's how you know it's good. Also, I wish people still said stuff like that, just in general. People in the 19th century were so much more eloquent. Thanks a lot, television.

No comments:

Post a Comment